REVIEW BY PEGI EYERS

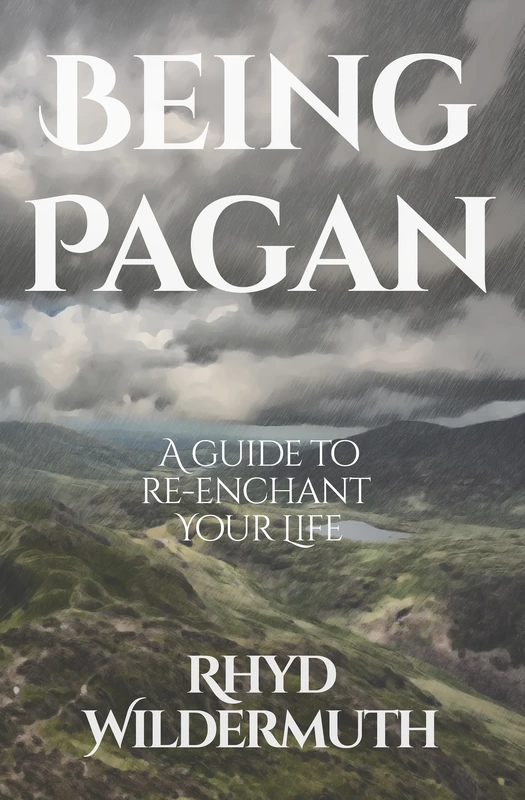

Being Pagan: A Guide to Re-Enchant Your Life

Rhyd Wildermuth // Ritona Press // 2021

As a long-time admirer of Rhyd Wildermuth's writing (and his expertise at publishing), it was incredibly exciting to read his new book on Pagan theory and practice. In our era of climate disaster and massive change, there is a critical need to recover the sacred, to reconnect to the earth and rejuvenate our ancestral wisdom, and Being Pagan is the perfect guidebook for the journey. Rhyd is a leader in Pagan Studies worldwide, and offers us a foundation for Pagan etymology, contemporary expressions, and how to reconnect to the cycles of the land in both urban and rural places. I especially appreciate his warm tone, and how the narrative – a weaving of prose and personal experience - feels like taking a tour with a caring companion.

Introducing us to the wooded hills of the Ardennes in pre-colonial Belgium - forests that were filled with deities, earth spirits and keystone species - he refutes the harmful myth of the wild as “backward and savage.” In fact, nature is sacred, and people living in harmony with the land have societies of stability and continuity, and the “ability to live in relative balance with the rest of the natural world around them, a trait completely absent and sorely missing in our modern world.” (Why This Book?) Without promoting Paganism as a religion or an identity, the goal of Being Pagan is to return us to a Pagan or animist understanding of the world, both in theory and praxis.

Introducing us to the wooded hills of the Ardennes in pre-colonial Belgium - forests that were filled with deities, earth spirits and keystone species - he refutes the harmful myth of the wild as “backward and savage.” In fact, nature is sacred, and people living in harmony with the land have societies of stability and continuity, and the “ability to live in relative balance with the rest of the natural world around them, a trait completely absent and sorely missing in our modern world.” (Why This Book?) Without promoting Paganism as a religion or an identity, the goal of Being Pagan is to return us to a Pagan or animist understanding of the world, both in theory and praxis.

Being Pagan: A Guide to Re-Enchant Your Life (video)

The first - and most basic step - is to track the moon, as these cycles influence our entire reality. For millennia, monthly rhythms have affected the patterns of time, the fertility cycle for women, and our psyches at the deepest level. Tides ruled by the moon provided aquatic diets for societies bonded to place, and today, the moon still influences our sleep and energy cycles. “The moon has been our light, our lamp in the darkness. It has also been our calendar, our clock, the primary way by which we measured the passing of time and the cycles of nature long before we divided our days into hours, and used numbers to date our lives.” (Knowing the Moon) Following the phases of the moon is not just esoteric knowledge, but how we place nature at the center of our lives. As Rhyd points out, our own energy ebbs and flows with the moon – for example, he has low energy at the new moon and just before. Keeping track of the moon tells us when to start or finish projects, when to be alone, and when to be sociable. It is very grounding to understand how our energy levels and behavior are affected by the moon, and how to live according to those cycles.

Rhyd outlines how Pagan life in harmony with the cycles of nature, or “natural time” became the enemy of the industrial revolution, and how the first capitalists created “machine time” to discipline the workers. Including the new idea of a “work ethic” these fabrications were also beneficial for the Church Fathers, who were intent on eradicating pagan festivals and beliefs based on natural cycles. Even today, the Calvinist idea that “idleness equals sin” is deeply ingrained, with our frenetic schedules and lack of rest or down time. And yet, as Rhyd explains, our reconnection to Pagan time is not that difficult to recover. There is no special technology or education required - we just have to observe the moon on a regular basis. “Seeing my own rhythms connected to these vaster and ancient celestial and earthly patterns, places me in time. Not in the time of clocks and human calendars, not in a particular month in a particular year, but in an ever-expanding moment of all of life’s existence.” (Reconnecting to Pagan Time)

Rhyd outlines how Pagan life in harmony with the cycles of nature, or “natural time” became the enemy of the industrial revolution, and how the first capitalists created “machine time” to discipline the workers. Including the new idea of a “work ethic” these fabrications were also beneficial for the Church Fathers, who were intent on eradicating pagan festivals and beliefs based on natural cycles. Even today, the Calvinist idea that “idleness equals sin” is deeply ingrained, with our frenetic schedules and lack of rest or down time. And yet, as Rhyd explains, our reconnection to Pagan time is not that difficult to recover. There is no special technology or education required - we just have to observe the moon on a regular basis. “Seeing my own rhythms connected to these vaster and ancient celestial and earthly patterns, places me in time. Not in the time of clocks and human calendars, not in a particular month in a particular year, but in an ever-expanding moment of all of life’s existence.” (Reconnecting to Pagan Time)

The chapter “Being of the Land” is a fascinating survey on the ongoing divide that originated in Roman times between the urban and pastoral, and the [so-called] primitive and civilized. Terms such as “pagans, heathens or savages” were used for millennia to colonize Indigenous peoples and other earth-emergent societies. In conjunction with civilization-building, Christian hegemony was the norm and “the other” were either eliminated, converted, oppressed or assimilated. And yet, tribal collectives have always resisted this brutality, and continue to affirm that being connected to the land is how we are supposed to be living. The urban/rural dichotomy has existed for millennia, but taking our cues from the natural world instead of the dictates of Empire will lead to the re-enchantment that we seek.

“Being Pagan, then, is being connected to the land in a way that stands outside of—and often in opposition to—the concerns of the urban and of Empire. Even though the official histories of humanity always focus on them, empires and the cities they form are mere temporary interruptions to a more organic and mostly unwritten history of human life.” (The Rhythms of the Land) Deep connection may include eating locally and taking long walks, and becoming more open to any traces of emotion that remain in our neighborhoods or regions, and what happened there in the past. There may be watersheds or trees that attract us, and others that push us away. Then by tracking our own daily moods and experiences, a pattern, or “body map” may appear, of how we are influenced by place. “And remember to look for the moon as you step through the land from which you are composed, and into which you will one day return.” (Reconnecting to Land)

The next chapter “Being Body” is a brilliant précis on the hegemonic concepts of duality that have caused us to become alienated and disconnected, both from the land and our own bodies. The rhythms and sounds of nature developed into the first human languages, but the shift from oral to written culture and the dominance of monotheist religions further compartment-alized the world. (When Verbs became Nouns) There is still an overwhelming and debilitating emphasis in our society on linear thinking and objectification, that can be traced to these early philosophies. And yet the timeless Pagan and animist worldview moves us back to a holistic weaving of the emotional and spiritual aspects of self with the physical body, to the somatics of internal awareness and body positivity. "We do not have bodies. We are bodies." (Being Body) Intellectual functions have their place, but meditation, bodywork, exercise, massage and other practices can teach us to pay more attention to our rootedness and our body. Also, spending time in nature allows us to become more grounded, and opens us to a wider range of sensory perception and intuitive flow, a form of bodily “knowing.” “Body itself is a process, not just a static object, the same way that nature is an active force, not an abstract and unchanging concept.” (How We Came to “Have” Bodies)

“Being Pagan, then, is being connected to the land in a way that stands outside of—and often in opposition to—the concerns of the urban and of Empire. Even though the official histories of humanity always focus on them, empires and the cities they form are mere temporary interruptions to a more organic and mostly unwritten history of human life.” (The Rhythms of the Land) Deep connection may include eating locally and taking long walks, and becoming more open to any traces of emotion that remain in our neighborhoods or regions, and what happened there in the past. There may be watersheds or trees that attract us, and others that push us away. Then by tracking our own daily moods and experiences, a pattern, or “body map” may appear, of how we are influenced by place. “And remember to look for the moon as you step through the land from which you are composed, and into which you will one day return.” (Reconnecting to Land)

The next chapter “Being Body” is a brilliant précis on the hegemonic concepts of duality that have caused us to become alienated and disconnected, both from the land and our own bodies. The rhythms and sounds of nature developed into the first human languages, but the shift from oral to written culture and the dominance of monotheist religions further compartment-alized the world. (When Verbs became Nouns) There is still an overwhelming and debilitating emphasis in our society on linear thinking and objectification, that can be traced to these early philosophies. And yet the timeless Pagan and animist worldview moves us back to a holistic weaving of the emotional and spiritual aspects of self with the physical body, to the somatics of internal awareness and body positivity. "We do not have bodies. We are bodies." (Being Body) Intellectual functions have their place, but meditation, bodywork, exercise, massage and other practices can teach us to pay more attention to our rootedness and our body. Also, spending time in nature allows us to become more grounded, and opens us to a wider range of sensory perception and intuitive flow, a form of bodily “knowing.” “Body itself is a process, not just a static object, the same way that nature is an active force, not an abstract and unchanging concept.” (How We Came to “Have” Bodies)

“Wolf and Oak” introduces us to the importance of a keystone species to the ecosystem, to the truth that sentient elements, plants and animals are considered “kin” by Indigenous, Pagan and animist worldviews, and that ritual and reciprocity sustains all life. The cycles of growing and harvesting in our homelands, the bounty of nature and our important connections to food, have always shaped our ways of knowing. Eventually, modernity transformed these ancient bonds with Earth Community into “servants and products.” “In our ravenous consumption we destroyed the keystones of many ecosystems, chased out the apex predators and felled the sacred trees, leaving less and less space for our kin to survive. The animist, Pagan relationship saw everything as mutual relation and obligation, whereas the modern way of thinking about the world is inherently selfish and human-centric.” (The Great Oak)

“Gods and Spirits” is a fascinating survey on dragons, giants and other mythical beings arising from formations in the land, and the blurring of lines between gods, land spirits, ancestors, and the forces in nature. In Pagan and Indigenous societies, “the existence of gods and spirits was part of the cultural fabric of life itself.” (What to Do About the Gods) The chapter “The Other” takes us on a captivating journey through the spheres of the occult, the practice of magic and “body memory,” and the acknowledgement that animists are capable of incredible feats when embedded in the natural world. Today, we can nurture the same magical abilities and gifts, such as intuition, insight, and messages from the dreamtime, by paying attention to what our bodies (aka our genii,, the unconscious, the spirits, dream callings) are saying. “Listening to the Other is the key to the Pagan framework of magic, of aligning consciousness to the unconscious in order to affect change.” (Listening to the Other)

Moving from objectivity to his own experience, with the chapter “The Fires of Meaning” Rhyd offers a deeply personal narrative on reaching communion with the Gods and other ancestral forces. The point he makes is that each seeker will make these connections and form relationships to the spirits in their own unique way. “Life is an enchanted thing, the body is capable of understanding things we rarely allow ourselves to experience, nature has a rhythm and song of its own, our ancestors understood things we desperately need to remember, the land speaks, and gods and spirits dwell everywhere. All this that I have written about I have learned because of these experiences, from letting myself be body and giving attention to the time of the moon, the seasons, and the stars rather than the logic of machines.” (What Willst Du?) Followed by an extraordinary summary of all the practices and modalities as outlined in Being Pagan, the chapter “Pagan Rituals” will “help you reclaim a sense of agency and active relation to the world.” (Pagan Rituals)

“Gods and Spirits” is a fascinating survey on dragons, giants and other mythical beings arising from formations in the land, and the blurring of lines between gods, land spirits, ancestors, and the forces in nature. In Pagan and Indigenous societies, “the existence of gods and spirits was part of the cultural fabric of life itself.” (What to Do About the Gods) The chapter “The Other” takes us on a captivating journey through the spheres of the occult, the practice of magic and “body memory,” and the acknowledgement that animists are capable of incredible feats when embedded in the natural world. Today, we can nurture the same magical abilities and gifts, such as intuition, insight, and messages from the dreamtime, by paying attention to what our bodies (aka our genii,, the unconscious, the spirits, dream callings) are saying. “Listening to the Other is the key to the Pagan framework of magic, of aligning consciousness to the unconscious in order to affect change.” (Listening to the Other)

Moving from objectivity to his own experience, with the chapter “The Fires of Meaning” Rhyd offers a deeply personal narrative on reaching communion with the Gods and other ancestral forces. The point he makes is that each seeker will make these connections and form relationships to the spirits in their own unique way. “Life is an enchanted thing, the body is capable of understanding things we rarely allow ourselves to experience, nature has a rhythm and song of its own, our ancestors understood things we desperately need to remember, the land speaks, and gods and spirits dwell everywhere. All this that I have written about I have learned because of these experiences, from letting myself be body and giving attention to the time of the moon, the seasons, and the stars rather than the logic of machines.” (What Willst Du?) Followed by an extraordinary summary of all the practices and modalities as outlined in Being Pagan, the chapter “Pagan Rituals” will “help you reclaim a sense of agency and active relation to the world.” (Pagan Rituals)

I especially appreciated the chapters in Being Pagan that covered issues I continue to research and examine in my own work. “Those Who Came Before” is a wonderful exploration on The Ancestors, including “rootlessness and even confusion about what ancestry means” in the Americas; how ancestral legacies today are usually focused on inherited wealth or health; ancestral trauma; displacement; diaspora; the ambiguity of claiming questionable ancestors; and how in Indigenous and Pagan societies one’s ancestry is considered beneficial or “part of the physical reality of a person’s life.” (The Meaning of Ancestors) A major part of communal ancestry is the passing on of traditional knowledge and values, but it is a process engaged in, by both the ancestors and their living descendants. It is fascinating to see how basic behaviors and beliefs can still manifest and adapt after many generations, to the lifestyles of today. Ancestral veneration, shrines, prayer, and speaking with the Ancestors are also important Pagan practices.

Finally, with the appendix “A Plague of Gods: Cultural Appropriation and the Resurgent Left Sacred” Rhyd tackles a controversial and contentious subject. Social justice activists today have embraced call-out culture to address the issue, but this approach is incredibly toxic, and adds additional layers of trauma to what modern folks are already carrying. Allies should still listen to the voices of those most affected by cultural appropriation, such as First Nations in the Americas, but fresh approaches such as Rhyd’s can add more balance to the conversation.

Overall, Being Pagan is an important guide to transforming the disconnect imposed on us by Empire by reclaiming pastoral time, and by reflecting the cycles of the land and the moon in our own experiences and Pagan traditions. We owe it to our collective ancestors to renew our connection to the land spirits, embrace an animist worldview, and embody re-enchantment in our lives. We need to stop seeing Earth Community as commodities and products but sacred kin, and practice the ancient rituals once again. “It's of course urgent that we return to this Pagan way of relating to our kin, but most of all it’s both utterly possible and a source of profound joy available to all.” (Being Kin) Highly Recommended.

Finally, with the appendix “A Plague of Gods: Cultural Appropriation and the Resurgent Left Sacred” Rhyd tackles a controversial and contentious subject. Social justice activists today have embraced call-out culture to address the issue, but this approach is incredibly toxic, and adds additional layers of trauma to what modern folks are already carrying. Allies should still listen to the voices of those most affected by cultural appropriation, such as First Nations in the Americas, but fresh approaches such as Rhyd’s can add more balance to the conversation.

Overall, Being Pagan is an important guide to transforming the disconnect imposed on us by Empire by reclaiming pastoral time, and by reflecting the cycles of the land and the moon in our own experiences and Pagan traditions. We owe it to our collective ancestors to renew our connection to the land spirits, embrace an animist worldview, and embody re-enchantment in our lives. We need to stop seeing Earth Community as commodities and products but sacred kin, and practice the ancient rituals once again. “It's of course urgent that we return to this Pagan way of relating to our kin, but most of all it’s both utterly possible and a source of profound joy available to all.” (Being Kin) Highly Recommended.

Being Pagan: A Guide to Re-Enchant Your Life is available >here<

paperback and digital copies

Pegi Eyers is the author of "Ancient Spirit Rising:

Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community"

an award-winning book that explores strategies for intercultural

competency, healing our relationships with Turtle Island First Nations, uncolonization, recovering an ecocentric worldview, rewilding, creating a sustainable future and reclaiming peaceful co-existence in Earth Community.

Available from Stone Circle Press or Amazon.

Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community"

an award-winning book that explores strategies for intercultural

competency, healing our relationships with Turtle Island First Nations, uncolonization, recovering an ecocentric worldview, rewilding, creating a sustainable future and reclaiming peaceful co-existence in Earth Community.

Available from Stone Circle Press or Amazon.