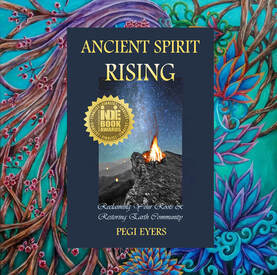

Thank you so much to Roots and Wings for including "Ancient Spirit Rising" on this illustrious list ~!

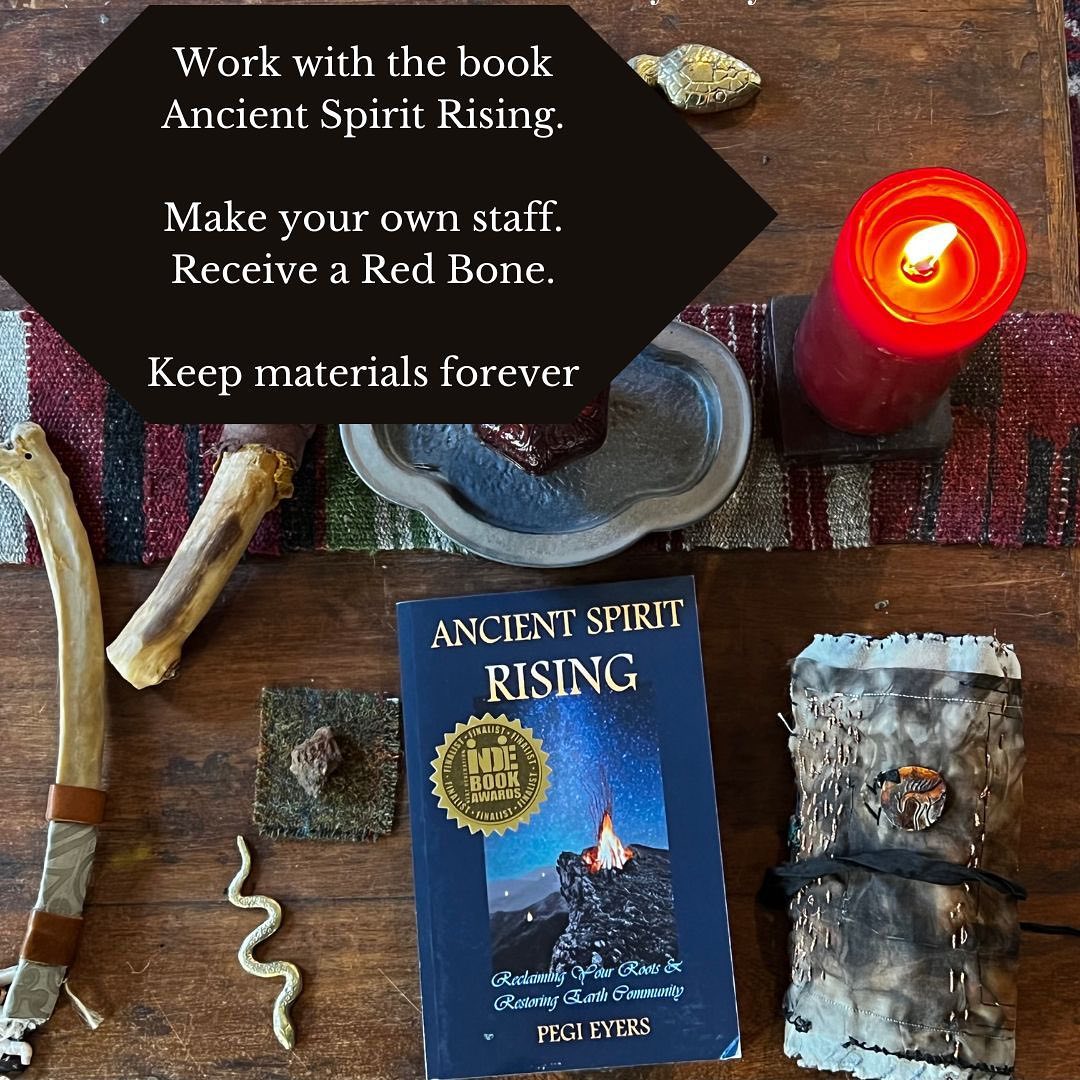

| Pegi Eyers is the author of "Ancient Spirit Rising: Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community," an award-winning book that explores strategies for uncolonization, rejecting Empire, social justice, ethnocultural identity, Apocalypse Studies, building land- emergent community & resilience in times of massive change. |