BRIAN FAWCETT

Reprint from The Journal of Wild Culture, Spring 1989

Your soul - don't leave home without it

I was sitting in one of the bars at Pearson Airport in Toronto, waiting for a flight and trying to dig my way out of the vague depression I experience whenever I travel. At the next table two men in business suits were talking.

“Did you get those futures under control before you left the office?” the older of them asked the other. The peculiar use of the word “future” instantly captured my attention. I noted that his suit was darker, and that his voice exuded seniority if not quite authority. Or maybe it’s just that I didn’t like the idea of this guy with futures and authority.

The other man seemed slightly uncomfortable with the question. “I tied down wheat and hog bellies, Hal,” he answered, using the man’s man as if it were a prayer rug he’d only recently gained the use of. “I’ve got the energies in my app. They’re all unstable as hell, and I thought we could work them over during the flight and make our move from Denver.”

Hal grimaced. “Can’t you handle this by yourself?” he asked, with a slight edge of irritation in his voice. “Hal, I need your help on this one,” the younger man whined. “I just don’t have enough experience in this kind of volatile market.”

Hal gazed at the younger man, coiling his body in the chair as if to impart a great truth – or to bite out his companion’s throat. “Experience no longer exists, my friend,” he said. “There is only data, and the daring to recognize when it becomes profitable information.”

Hal closed his alligator-skin briefcase as he said it, flipped a five-dollar bill into the center of the table and placed his empty whisky glass on top of it. The conference was over. Both men slid out from behind the table, tugged their suits straight and walked to the entrance. The younger man walked just behind Hal’s shoulder. He still didn’t have a name.

The little jerk is practicing military deference, I thought, as I watched them disappear into the terminal crowd. Disgusting. I was glad they were leaving my universe. Then I realized that it was their universe I was in. At least I could be grateful that they were leaving the small part of it I was temporarily occupying, and I didn’t want to know where they were going. Straight to hell, for all I cared. But with a stopover in Denver to manipulate the future.

To tell the truth, I didn’t want to know where any of the grinning freaks still sitting in the lounge were going, or where they’d been, or why. I didn’t want to be there. I wanted to be at home where I could think straight.

Travel scrambles my brain circuitry, air travel more than any other kind. There’s probably no other place on earth I dislike more than airports. They make me grumpier than I normally

am, and I’m a reasonably grumpy person. I’d been travelling for weeks, and right then I would give a lot to be non-conscious, and more if I could be at home. I certainly didn’t want to talk to anyone.

I wasn’t to get my wish. An elderly man entered the bar and stood near the entrance, scanning the scattered clientele. Almost without hesitation, he focused on me. Our eyes met briefly. I broke contact first, developing a sudden urge to determine the species of wood used in the bar décor. Walnut, I decided. Most of it no doubt one-eighth-inch veneer. The wall panels probably ersatz walnut, the kind they photograph onto chipboard.

Unpleasant-looking old codger, I decided as I watched him make his way to my table. Something had gone sour in his face a long time ago - his mouth was permanently resolved, as if he’d made an early but fundamental decision that life was not good, and the decision had been leaking a mild toxin into his facial tissues ever since. He appeared to be in his late seventies,

but there was nothing in his body language and demeanor

that indicated the kind of weathering that creates the oaky mild wisdom that sometimes comes with old age. Nothing had been softened or enriched by time. It had only petrified or scraped dry. I didn’t like his looks at all.

The briefcase he carried intensified that dislike. It was an expensive leather one, neutral coloured, narrow, and soft-sheened. No laptop in that one. This guy was from senior management.

Despite myself I wondered what was inside it. Plans for an industrial takeover? Plans for the end of the world? Then I remembered that he was coming to talk to me. He couldn’t be an executive, and the briefcase would therefore be filled with pamphlets. Pyramid sales, or some course on executive-building. Or worse – religious pamphlets. He had the look of a man bent on saving someone.

“Did you get those futures under control before you left the office?” the older of them asked the other. The peculiar use of the word “future” instantly captured my attention. I noted that his suit was darker, and that his voice exuded seniority if not quite authority. Or maybe it’s just that I didn’t like the idea of this guy with futures and authority.

The other man seemed slightly uncomfortable with the question. “I tied down wheat and hog bellies, Hal,” he answered, using the man’s man as if it were a prayer rug he’d only recently gained the use of. “I’ve got the energies in my app. They’re all unstable as hell, and I thought we could work them over during the flight and make our move from Denver.”

Hal grimaced. “Can’t you handle this by yourself?” he asked, with a slight edge of irritation in his voice. “Hal, I need your help on this one,” the younger man whined. “I just don’t have enough experience in this kind of volatile market.”

Hal gazed at the younger man, coiling his body in the chair as if to impart a great truth – or to bite out his companion’s throat. “Experience no longer exists, my friend,” he said. “There is only data, and the daring to recognize when it becomes profitable information.”

Hal closed his alligator-skin briefcase as he said it, flipped a five-dollar bill into the center of the table and placed his empty whisky glass on top of it. The conference was over. Both men slid out from behind the table, tugged their suits straight and walked to the entrance. The younger man walked just behind Hal’s shoulder. He still didn’t have a name.

The little jerk is practicing military deference, I thought, as I watched them disappear into the terminal crowd. Disgusting. I was glad they were leaving my universe. Then I realized that it was their universe I was in. At least I could be grateful that they were leaving the small part of it I was temporarily occupying, and I didn’t want to know where they were going. Straight to hell, for all I cared. But with a stopover in Denver to manipulate the future.

To tell the truth, I didn’t want to know where any of the grinning freaks still sitting in the lounge were going, or where they’d been, or why. I didn’t want to be there. I wanted to be at home where I could think straight.

Travel scrambles my brain circuitry, air travel more than any other kind. There’s probably no other place on earth I dislike more than airports. They make me grumpier than I normally

am, and I’m a reasonably grumpy person. I’d been travelling for weeks, and right then I would give a lot to be non-conscious, and more if I could be at home. I certainly didn’t want to talk to anyone.

I wasn’t to get my wish. An elderly man entered the bar and stood near the entrance, scanning the scattered clientele. Almost without hesitation, he focused on me. Our eyes met briefly. I broke contact first, developing a sudden urge to determine the species of wood used in the bar décor. Walnut, I decided. Most of it no doubt one-eighth-inch veneer. The wall panels probably ersatz walnut, the kind they photograph onto chipboard.

Unpleasant-looking old codger, I decided as I watched him make his way to my table. Something had gone sour in his face a long time ago - his mouth was permanently resolved, as if he’d made an early but fundamental decision that life was not good, and the decision had been leaking a mild toxin into his facial tissues ever since. He appeared to be in his late seventies,

but there was nothing in his body language and demeanor

that indicated the kind of weathering that creates the oaky mild wisdom that sometimes comes with old age. Nothing had been softened or enriched by time. It had only petrified or scraped dry. I didn’t like his looks at all.

The briefcase he carried intensified that dislike. It was an expensive leather one, neutral coloured, narrow, and soft-sheened. No laptop in that one. This guy was from senior management.

Despite myself I wondered what was inside it. Plans for an industrial takeover? Plans for the end of the world? Then I remembered that he was coming to talk to me. He couldn’t be an executive, and the briefcase would therefore be filled with pamphlets. Pyramid sales, or some course on executive-building. Or worse – religious pamphlets. He had the look of a man bent on saving someone.

As he approached, I almost wished the two electronic executives hadn’t left. I could have pointed to them – see, look! These guys need your literature, not me. I would have had my objections brushed aside. The old man was fixed on me like the Ancient Mariner on his wedding guest. Oh, Christ, I thought as he closed in.

“Christ can't help you,” he said in a crisp British accent. “But perhaps I might.”

I'd have rolled my eyes if there'd been anyone around to do it for. There wasn't, and anyway, it was too late. My elderly assailant was staring at me as if he could see through me. Maybe he could. He'd already read my mind.

“Bloody airports,” he said.

“That's what I've been thinking,” I answered before I could stop myself.

“l'm aware of that,” he said, his mouth sucking on his cosmic lemon again. “You're impressionable. That's why I chose you.”

“Go away,” I said, feebly. “l don't want to be chosen.”

''Well,” he replied, fixing me with his cold stare, “You've been chosen. Stop snivelling and listen.”

Maybe, I calculated, a little show of aggression will get him to leave me alone. He cut that thought off.

“Don't try aggression. It won't get you anywhere. I'm here to help you, and there's no avoiding it.”

“l don't need help. I'm just fine. Let me wait for my stupid plane in ignorance.”

“Stupid ignorance.”

“Pardon me?”

“You heard me,” he said. “Planes aren't stupid. They aren't anything at all, one way or the other. They're machines. But you're stupid if you desire ignorance.”

Well, I thought, at least he's not a born-again Christian. They love ignorance. It's their operational precondition. “l desire you to leave me alone,” I mumbled. “That's what I desire.”

"You're already far too alone. That's why I'm here."

This time I did roll my eyes. To hell with him. “Go away.” I said. “Cease and desist. Let me bear the agony of travel unmolested by your wisdom.”

“Exactly,” he said.

“What?”

“Travel is agony.”

“You came here to tell me that?”

He lowered himself gingerly into the chair opposite me. With our eyes at the same level I felt slightly less uncomfortable, but I still wanted him to go away. “No,” he said solemnly. “l came to tell you why.”

“You came to tell me why travel is agony?” I said. “l know why. It's because weird people are always hitting on me. Weird people like you.”

The old man was unperturbed. “That isn't why, you silly ass, and you know it.”

I didn't know, and I told him so. Then I repeated my request that he leave me to my discomforts.

“lt's actually rather simple,” he said. “lt has to do with the travel abilities of the human soul.”

Shit, I thought. “You're a Rosicrucian, right?”

“No. Please listen carefully. The reason why you feel disoriented when you travel is because your soul isn't travelling with you.”

“l don't have a soul,” I said. That didn't sound right, so I corrected myself - better to discuss theology than personality. “There's no evidence for the existence of the soul.”

At first he seemed to go for it. “There's no material evidence for the existence of the soul, you mean. Not conventional evidence, anyway. Don't underestimate me. I'm not a stupid man. We're both familiar with the philosophical arguments about the existence of the soul, which all proceed deductively, or by negation. My evidence is quite different.”

“Go on,” I said, my curiosity aroused despite my misgivings.

“Some of the native cultures on your West Coast have a saying. It's this: 'When one abandons their home ground, they lose their soul.' Now, that sounds like little more than a localist slogan until you examine a few illustrations.”

“l'm listening.” I was listening, against my will. How did he know I was from the West Coast?

“lf a multinational corporation were to purchase a plot of land next to the one you're living on, and announced that it intended to excavate a huge pit on it, what would you do?”

“Depends,” I said.

“On what?”

“Well, on what my piece of property was worth to me. And on how much the developer was willing to give me to leave.”

“Multinationals don't give anything away. And how is value assigned to what you're calling property?”

He paused for a second, as if to let the possible taxonomies penetrate. “Let me rephrase my question slightly. Imagine that there are two people living next to the target land. One of them was born on the spot, and his ancestors have lived there for at least several generations. The other person has lived there for less than two years. Which one would be more likely to fight the multinational, and which one would be more effective?”

“Christ can't help you,” he said in a crisp British accent. “But perhaps I might.”

I'd have rolled my eyes if there'd been anyone around to do it for. There wasn't, and anyway, it was too late. My elderly assailant was staring at me as if he could see through me. Maybe he could. He'd already read my mind.

“Bloody airports,” he said.

“That's what I've been thinking,” I answered before I could stop myself.

“l'm aware of that,” he said, his mouth sucking on his cosmic lemon again. “You're impressionable. That's why I chose you.”

“Go away,” I said, feebly. “l don't want to be chosen.”

''Well,” he replied, fixing me with his cold stare, “You've been chosen. Stop snivelling and listen.”

Maybe, I calculated, a little show of aggression will get him to leave me alone. He cut that thought off.

“Don't try aggression. It won't get you anywhere. I'm here to help you, and there's no avoiding it.”

“l don't need help. I'm just fine. Let me wait for my stupid plane in ignorance.”

“Stupid ignorance.”

“Pardon me?”

“You heard me,” he said. “Planes aren't stupid. They aren't anything at all, one way or the other. They're machines. But you're stupid if you desire ignorance.”

Well, I thought, at least he's not a born-again Christian. They love ignorance. It's their operational precondition. “l desire you to leave me alone,” I mumbled. “That's what I desire.”

"You're already far too alone. That's why I'm here."

This time I did roll my eyes. To hell with him. “Go away.” I said. “Cease and desist. Let me bear the agony of travel unmolested by your wisdom.”

“Exactly,” he said.

“What?”

“Travel is agony.”

“You came here to tell me that?”

He lowered himself gingerly into the chair opposite me. With our eyes at the same level I felt slightly less uncomfortable, but I still wanted him to go away. “No,” he said solemnly. “l came to tell you why.”

“You came to tell me why travel is agony?” I said. “l know why. It's because weird people are always hitting on me. Weird people like you.”

The old man was unperturbed. “That isn't why, you silly ass, and you know it.”

I didn't know, and I told him so. Then I repeated my request that he leave me to my discomforts.

“lt's actually rather simple,” he said. “lt has to do with the travel abilities of the human soul.”

Shit, I thought. “You're a Rosicrucian, right?”

“No. Please listen carefully. The reason why you feel disoriented when you travel is because your soul isn't travelling with you.”

“l don't have a soul,” I said. That didn't sound right, so I corrected myself - better to discuss theology than personality. “There's no evidence for the existence of the soul.”

At first he seemed to go for it. “There's no material evidence for the existence of the soul, you mean. Not conventional evidence, anyway. Don't underestimate me. I'm not a stupid man. We're both familiar with the philosophical arguments about the existence of the soul, which all proceed deductively, or by negation. My evidence is quite different.”

“Go on,” I said, my curiosity aroused despite my misgivings.

“Some of the native cultures on your West Coast have a saying. It's this: 'When one abandons their home ground, they lose their soul.' Now, that sounds like little more than a localist slogan until you examine a few illustrations.”

“l'm listening.” I was listening, against my will. How did he know I was from the West Coast?

“lf a multinational corporation were to purchase a plot of land next to the one you're living on, and announced that it intended to excavate a huge pit on it, what would you do?”

“Depends,” I said.

“On what?”

“Well, on what my piece of property was worth to me. And on how much the developer was willing to give me to leave.”

“Multinationals don't give anything away. And how is value assigned to what you're calling property?”

He paused for a second, as if to let the possible taxonomies penetrate. “Let me rephrase my question slightly. Imagine that there are two people living next to the target land. One of them was born on the spot, and his ancestors have lived there for at least several generations. The other person has lived there for less than two years. Which one would be more likely to fight the multinational, and which one would be more effective?”

Those weren't very hard questions. “The homer, naturally. In both cases. They would know more, and would be more likely to persist when the going got tough.”

"Well,” he said, “that's what the human soul is, and where it resides. It's a relationship between consciousness and material objects. lt is a sensibility created by familiarity and loyalty to places and things.”

“Interesting,” I said. “But what's this got to do flying, or with hanging around airports?"

“Quite a lot. Think of airports as generative structures for homelessness. Repositories of physical and intellectual landscape alienation. Petri dishes of delocalized despair. Soul debris depots. First of all, airports are pretty much the same across the world; so, in a sense they breed a kind of contrary stereotype: home for the homeless. That involves several more things. The kind of alienated energy constantly passing through them, and the residual buildup of it.”

“This is getting pretty far-fetched,” I muttered.

“lt's unconventional, that's all. I could explain the physics to you, but you're not a physicist. I'm explaining it in urban planning terms and in anthropological terms, which is within your range of nominal expertise.”

Right again, I thought, wondering if he was from the CIA or the CSIS. Too old, I decided. And too accurate. Far too weirdly accurate.

“The technology for creating anti-localist experiential structures has existed now for some years. The motivation researchers inside the major consumer corporations have been using it for decades without really recognizing what they've got. They understand, for instance, that there is a fundamental human need for familiarity and solidarity, and they've learned to manipulate its focus from landscapes and kinship or social loyalty structures to consumer stereotypes. They're like terrorists with a plutonium bomb. They can't get it to explode, but the more they tinker with it the more radiation gets released.”

“Give me another example.”

“Well, Disneyland is the best one.”

“Never been there,” I said. “Never will, either.”

“Millions have, and millions more are going to go. Disneyland is a kind of laundered, cartoonized replication of the world. It allows people to experience history and geography without physical risk or threat to their value structures. Everything is translated into a very simplified version of basic Western consumer capitalist values. Sort of like fishsticks or chicken nuggets. Instead of sharks you get shark fishsticks.”

“You're losing me here. What’s this got to do with airports, or the human soul?”

'Well, think of it - Disneyland, or consumerism in general, as an alternative to the human soul. Without a soul, as I defined it earlier - landscape and history have no meaning - no critical frame of reference or consequences.”

“Uh huh. That I can see. But maybe that's the way things are going. Maybe it's a natural evolution of the species.”

“Oh, an evolution, maybe. Not a natural one. It might also be a devolution, or a convolution.”

“Those don't seem to be risks we can avoid. They're happening. No way to stop them.”

“l'm suggesting only that they should be understood. Or rather, that you understand them.”

"Well,” he said, “that's what the human soul is, and where it resides. It's a relationship between consciousness and material objects. lt is a sensibility created by familiarity and loyalty to places and things.”

“Interesting,” I said. “But what's this got to do flying, or with hanging around airports?"

“Quite a lot. Think of airports as generative structures for homelessness. Repositories of physical and intellectual landscape alienation. Petri dishes of delocalized despair. Soul debris depots. First of all, airports are pretty much the same across the world; so, in a sense they breed a kind of contrary stereotype: home for the homeless. That involves several more things. The kind of alienated energy constantly passing through them, and the residual buildup of it.”

“This is getting pretty far-fetched,” I muttered.

“lt's unconventional, that's all. I could explain the physics to you, but you're not a physicist. I'm explaining it in urban planning terms and in anthropological terms, which is within your range of nominal expertise.”

Right again, I thought, wondering if he was from the CIA or the CSIS. Too old, I decided. And too accurate. Far too weirdly accurate.

“The technology for creating anti-localist experiential structures has existed now for some years. The motivation researchers inside the major consumer corporations have been using it for decades without really recognizing what they've got. They understand, for instance, that there is a fundamental human need for familiarity and solidarity, and they've learned to manipulate its focus from landscapes and kinship or social loyalty structures to consumer stereotypes. They're like terrorists with a plutonium bomb. They can't get it to explode, but the more they tinker with it the more radiation gets released.”

“Give me another example.”

“Well, Disneyland is the best one.”

“Never been there,” I said. “Never will, either.”

“Millions have, and millions more are going to go. Disneyland is a kind of laundered, cartoonized replication of the world. It allows people to experience history and geography without physical risk or threat to their value structures. Everything is translated into a very simplified version of basic Western consumer capitalist values. Sort of like fishsticks or chicken nuggets. Instead of sharks you get shark fishsticks.”

“You're losing me here. What’s this got to do with airports, or the human soul?”

'Well, think of it - Disneyland, or consumerism in general, as an alternative to the human soul. Without a soul, as I defined it earlier - landscape and history have no meaning - no critical frame of reference or consequences.”

“Uh huh. That I can see. But maybe that's the way things are going. Maybe it's a natural evolution of the species.”

“Oh, an evolution, maybe. Not a natural one. It might also be a devolution, or a convolution.”

“Those don't seem to be risks we can avoid. They're happening. No way to stop them.”

“l'm suggesting only that they should be understood. Or rather, that you understand them.”

The waiter was standing beside the table. “ls this man bothering you, Sir?” he asked, motioning at the old man.

“No,” I said. “Bring me another beer, will you?”

“What brand would you like, Sir?”

The old man cut in. “Bring us two glasses of soda water. That will be just fine.”

The waiter glanced sharply at me for confirmation. “Okay,” I said. “He's my long-lost uncle. Bring us soda water if he says so.”

“Don't be impertinent,” the old man snapped. “Now. Let's get back to our discussion. The human soul has a very specific property that makes it hostile to contemporary reality.”

“And what's that property?”

“lt doesn't fly.”

The old man stared at me coolly, as if expecting a response. I couldn't think of anything to say. lnstead, I sorted through the logic of his previous statements. Consistent.

“Are you speaking metaphorically, or are you making a declarative statement to the effect that a human soul is prohibited from boarding an aircraft?”

“What's the difference?”

“Well, I'd be interested to know why, if it can't board aircraft. There's nothing in the IATA regulations to say that. l've read them. And surely it isn't the lack of seats.”

“The soul is not an adjunct to the human body. It is not an automatic possession. It can be earned or nurtured, just as it can be lost or destroyed by misadventure. But it is not automatically inherited. Think of it as an external database that by its nature cannot be transported.”

“Oh,” I said, shifting in my chair as the waiter slid the two soda waters onto the table. I dropped him a five and he disappeared. “That makes sense, I suppose. So where is my soul?”

The old man frowned, and began to stare at the back of his hand as if it were a television screen. After a moment's consideration, he looked up again. “You've been travelling for thirteen days?”

I nodded. “About that.”

“Your soul is just east of Kamloops, B.C., walking along the TransCanada Highway.”

He said it with such authority that I didn't laugh. “lt's following me?”

“Of course. What else would it do?”

“You said that the soul is landscape-derived. Why wouldn't it stay on home ground and wait?”

“l said that it was the creation of a relationship between a body of understanding and a place. Once created, it can't survive without its body of understanding, so to speak. So it follows it, tries to locate it.”

“All the way from Vancouver to Kamloops. 375 miles.”

“Your particular soul is a fast walker,” he said, without a trace of irony. “lt would walk all the way here, unless you underwent a personality change, or a loss of memory, or you died.”

“Then it would die?”

“Not exactly. It would try to return to the conditions of its creation.”

“And do what?”

“No,” I said. “Bring me another beer, will you?”

“What brand would you like, Sir?”

The old man cut in. “Bring us two glasses of soda water. That will be just fine.”

The waiter glanced sharply at me for confirmation. “Okay,” I said. “He's my long-lost uncle. Bring us soda water if he says so.”

“Don't be impertinent,” the old man snapped. “Now. Let's get back to our discussion. The human soul has a very specific property that makes it hostile to contemporary reality.”

“And what's that property?”

“lt doesn't fly.”

The old man stared at me coolly, as if expecting a response. I couldn't think of anything to say. lnstead, I sorted through the logic of his previous statements. Consistent.

“Are you speaking metaphorically, or are you making a declarative statement to the effect that a human soul is prohibited from boarding an aircraft?”

“What's the difference?”

“Well, I'd be interested to know why, if it can't board aircraft. There's nothing in the IATA regulations to say that. l've read them. And surely it isn't the lack of seats.”

“The soul is not an adjunct to the human body. It is not an automatic possession. It can be earned or nurtured, just as it can be lost or destroyed by misadventure. But it is not automatically inherited. Think of it as an external database that by its nature cannot be transported.”

“Oh,” I said, shifting in my chair as the waiter slid the two soda waters onto the table. I dropped him a five and he disappeared. “That makes sense, I suppose. So where is my soul?”

The old man frowned, and began to stare at the back of his hand as if it were a television screen. After a moment's consideration, he looked up again. “You've been travelling for thirteen days?”

I nodded. “About that.”

“Your soul is just east of Kamloops, B.C., walking along the TransCanada Highway.”

He said it with such authority that I didn't laugh. “lt's following me?”

“Of course. What else would it do?”

“You said that the soul is landscape-derived. Why wouldn't it stay on home ground and wait?”

“l said that it was the creation of a relationship between a body of understanding and a place. Once created, it can't survive without its body of understanding, so to speak. So it follows it, tries to locate it.”

“All the way from Vancouver to Kamloops. 375 miles.”

“Your particular soul is a fast walker,” he said, without a trace of irony. “lt would walk all the way here, unless you underwent a personality change, or a loss of memory, or you died.”

“Then it would die?”

“Not exactly. It would try to return to the conditions of its creation.”

“And do what?”

For the first time, the old man seemed slightly embarrassed. “lt would, er, haunt. For a while. Nothing nasty, mind you. You may have noticed that places where people have lived a long time have a certain eerie coldness after they've gone.”

I had, but I didn't say so. After my parents left the small town I grew up in, their old house had that quality.

“That's right,” he said. “Almost a sense of betrayal. Yet the old places have always welcomed you back.”

He was right. But then I've managed to visit the old places every year or so since I left.

“l know that. They sense the kinship of your present soul.”

I was getting used to having him read my mind. “l usually fly up there. That means my soul isn't with me.”

“Smell,” he answered. “They smell you, because you're from there. As a point of technical information, so is your soul.”

“So what happens when I leave here and go home? Does my soul see me flying over it and start walking back?”

“Well, it senses it rather than sees you. That's why you feel disoriented for several weeks after a long trip. And that's why there's a strong sense of mental disturbance for a few hours when it actually arrives back.”

“Sort of like re-entry impact, no? It must be pissed off when it arrives. All that walking for nothing.”

“Yes. Quite. From its point of perception. And of course I needn't add that touring is not recreation for the human soul.”

I had, but I didn't say so. After my parents left the small town I grew up in, their old house had that quality.

“That's right,” he said. “Almost a sense of betrayal. Yet the old places have always welcomed you back.”

He was right. But then I've managed to visit the old places every year or so since I left.

“l know that. They sense the kinship of your present soul.”

I was getting used to having him read my mind. “l usually fly up there. That means my soul isn't with me.”

“Smell,” he answered. “They smell you, because you're from there. As a point of technical information, so is your soul.”

“So what happens when I leave here and go home? Does my soul see me flying over it and start walking back?”

“Well, it senses it rather than sees you. That's why you feel disoriented for several weeks after a long trip. And that's why there's a strong sense of mental disturbance for a few hours when it actually arrives back.”

“Sort of like re-entry impact, no? It must be pissed off when it arrives. All that walking for nothing.”

“Yes. Quite. From its point of perception. And of course I needn't add that touring is not recreation for the human soul.”

“Look,” I said, watching a tall man about my age sidle up to the bar and drop his overnight bag at his feet. There was something familiar about him, but I couldn't quire place it. He was dressed in blue jeans and a weathered brown leather jacket, and was flipping an American Express card between his thumb and forefinger: the global village Visigoth. He looked even more exhausted and disoriented than I'd been feeling. “All day, I've had this sense that I might at any moment go spinning off my axis. Does this have anything to do with the temporary separation from my soul?”

“Surely. Most of your physical and emotional interface nodes - the points that process incoming data - are unavailable, because those are afforded - lubricated as it were - by your soul. You're relying on stored intellectual fuel to keep you balanced right now. That’s why the longer you travel, the more likely you are to commit purely selfish acts, or to make decisions on a purely abstract basis. Or other kinds of stupid behaviors I needn't spell out for you. There’s nothing mystical about any of this. It’s coldly pragmatic.”

“You're suggesting that the soul is an inherent containment technology that operates in typical fashion, right? And that there are possible strategies for nurturing the soul - mine or anyone else's?”

'Yes. It's very simple. Travel as little as you can, for one. And never travel for purposes of geographical avoidance.”

“Huh?”

“One of the really evil practices consumerism supports is the practice of travelling to exotic destinations in order to avoid the reality of everyday life. Most people do that precisely at the

point where they should begin to investigate the particularities around them. And those pleasure ghettos are the worst. Two weeks at CIub Med will kill a weak human soul, or an incipient one. That's a far greater danger than herpes, which is what most people who go to those places worry about.”

“l think most of them already have herpes, actually.”

That got the smallest trace of a smile, but not for long. “That’s your joke. I have no precise data on that question. As a matter of fact,” he said, finishing his soda water and getting to his feet. “l'm pretty well out of relevant information.”

I half-expected him to vanish. I even closed my eyes to see if he would. “lt's been, er, a slice,” I said.

“No it hasn't,” he said. “This is not a mystical experience. Everything I've told you can be secured by operational data. It’s a question of accurate processing. I've merely offered you the metaphoric software.”

“Whatever you say.”

I closed my eves again, feeling weary and disoriented. When I opened them, the global village Visigoth at the bar was gone. In his place was the man I'd been talking to, dressed in the

Visigoth's costume. He was even flipping the Am Ex card, looking around the bar for someone else to hit on.

I had a plane to catch. And trudging along in the cool evening somewhere in the middle of the Rocky Mountains, I half -believed I had a soul to placate. Or, for the first time in my life, a soul to disbelieve in.

“Surely. Most of your physical and emotional interface nodes - the points that process incoming data - are unavailable, because those are afforded - lubricated as it were - by your soul. You're relying on stored intellectual fuel to keep you balanced right now. That’s why the longer you travel, the more likely you are to commit purely selfish acts, or to make decisions on a purely abstract basis. Or other kinds of stupid behaviors I needn't spell out for you. There’s nothing mystical about any of this. It’s coldly pragmatic.”

“You're suggesting that the soul is an inherent containment technology that operates in typical fashion, right? And that there are possible strategies for nurturing the soul - mine or anyone else's?”

'Yes. It's very simple. Travel as little as you can, for one. And never travel for purposes of geographical avoidance.”

“Huh?”

“One of the really evil practices consumerism supports is the practice of travelling to exotic destinations in order to avoid the reality of everyday life. Most people do that precisely at the

point where they should begin to investigate the particularities around them. And those pleasure ghettos are the worst. Two weeks at CIub Med will kill a weak human soul, or an incipient one. That's a far greater danger than herpes, which is what most people who go to those places worry about.”

“l think most of them already have herpes, actually.”

That got the smallest trace of a smile, but not for long. “That’s your joke. I have no precise data on that question. As a matter of fact,” he said, finishing his soda water and getting to his feet. “l'm pretty well out of relevant information.”

I half-expected him to vanish. I even closed my eyes to see if he would. “lt's been, er, a slice,” I said.

“No it hasn't,” he said. “This is not a mystical experience. Everything I've told you can be secured by operational data. It’s a question of accurate processing. I've merely offered you the metaphoric software.”

“Whatever you say.”

I closed my eves again, feeling weary and disoriented. When I opened them, the global village Visigoth at the bar was gone. In his place was the man I'd been talking to, dressed in the

Visigoth's costume. He was even flipping the Am Ex card, looking around the bar for someone else to hit on.

I had a plane to catch. And trudging along in the cool evening somewhere in the middle of the Rocky Mountains, I half -believed I had a soul to placate. Or, for the first time in my life, a soul to disbelieve in.

By Robin Ridington

Location exists in time as well as in place. Local knowledge is obviously local because it takes place, but it is also local because of a centered sense of time. Almost universally, the time of people who are Indigenous to a place is mythic time, a dreamtime, thought-time, a time of mind. Dreamtime imagines a deeper geography than that of the waking mind. The Tinkerbelle soul of sensation, dragged as it is from step to step by a body's inexorable sequentiality and ultimate failure, must measure time in a currency of distance. (After thirteen days, “Your soul is just east of Kamloops, B.C., walking along the TransCanada Highway.”)

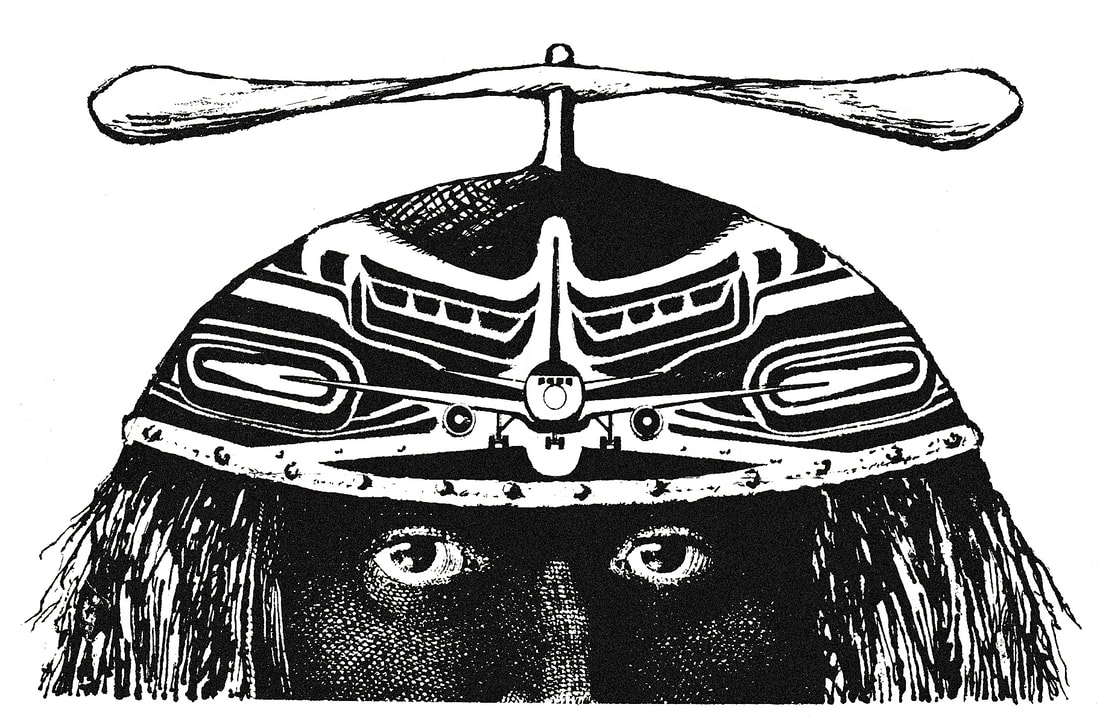

Among First Nations on Turtle Island, or North America, certain men and women are gifted to act as spirit guides to the mythic dimension. (Anthropologists have labelled them shamans, and Mircea Eliade called them "Psychopomps.") The Dunne-za of the Peace River country call these people Naacheen, or Dreamers. The time and space in which the Dreamers travel is different from the time and space in which we ordinarily experience the world. Dreamers travel by what Eliade gropingly called “magical flight.”

They move within the multiple possibilities of a time and space that is not imprisoned by the body's sequentiality. They make connections by similarity, opposition, reflection, resonance, and remembrance, rather than by physical contiguity alone. They move in a geography of the mind. They know how to separate experience from sensation.

The places that a Dreamer knows are connected logically rather than physically. They fit together in the way that memory and anticipation fit together. They fit together within a mosaic of meaning. When a Dreamer travels, he or she “grabs hold of a song with the mind” and leaves the body secure in its appointed place on earth. Dreamers are different from ordinary people only in that they have studied and learned the turns of Yagatunne, the Trail to Heaven. They understand how to come back from the dreamtime world. They come back to the place in which a physical body remains alive to receive the returning soul. They can leave their bodies and come back to them without dying. They can fly out of ordinary time into the essential time of myth.

Dreamers talk about their experiences using metaphors from nature, and from the dimensionality of a physical world. A Dreamer's cosmic axis spreads and threads the four directions into an imaginary hole at the center of things, a hole at the center of time as well as of space. Four directions and three worlds converge upon the idea of seven. That idea is the world's germinal center. This idea animates the experience of winds and silences, still water and cascades, animal persons, and persons of the human kind. That idea is the principle of creation, Yage-Sateen, the motionless idea of a center around which even dimensionality itself turns.

Among First Nations on Turtle Island, or North America, certain men and women are gifted to act as spirit guides to the mythic dimension. (Anthropologists have labelled them shamans, and Mircea Eliade called them "Psychopomps.") The Dunne-za of the Peace River country call these people Naacheen, or Dreamers. The time and space in which the Dreamers travel is different from the time and space in which we ordinarily experience the world. Dreamers travel by what Eliade gropingly called “magical flight.”

They move within the multiple possibilities of a time and space that is not imprisoned by the body's sequentiality. They make connections by similarity, opposition, reflection, resonance, and remembrance, rather than by physical contiguity alone. They move in a geography of the mind. They know how to separate experience from sensation.

The places that a Dreamer knows are connected logically rather than physically. They fit together in the way that memory and anticipation fit together. They fit together within a mosaic of meaning. When a Dreamer travels, he or she “grabs hold of a song with the mind” and leaves the body secure in its appointed place on earth. Dreamers are different from ordinary people only in that they have studied and learned the turns of Yagatunne, the Trail to Heaven. They understand how to come back from the dreamtime world. They come back to the place in which a physical body remains alive to receive the returning soul. They can leave their bodies and come back to them without dying. They can fly out of ordinary time into the essential time of myth.

Dreamers talk about their experiences using metaphors from nature, and from the dimensionality of a physical world. A Dreamer's cosmic axis spreads and threads the four directions into an imaginary hole at the center of things, a hole at the center of time as well as of space. Four directions and three worlds converge upon the idea of seven. That idea is the world's germinal center. This idea animates the experience of winds and silences, still water and cascades, animal persons, and persons of the human kind. That idea is the principle of creation, Yage-Sateen, the motionless idea of a center around which even dimensionality itself turns.

Elders of the Dunne-za told me that a person who steps into a whiteman's vehicle loses contact with the trail that his or her life takes on this earth. This trail begins with a child's very first steps. The Cree still ritualize these first steps in a ceremony of “walking the child” into the world, in a new pair of moccasins. The Dunne-za used to bury an old person in new moccasins for his or her journey along Yagatunne, the Trail to Heaven. Only the Dreamer is able to leave the trail of his or her physical body on earth and return safely. When ordinary people lose their tracks to those of a vehicle among the multitude of vehicles, they are no longer able to find the Trail to Heaven. The old people who lived most of their lives hundreds of miles from the nearest roads were in agreement that the ghosts of people who died in car accidents, might spend years walking up and down the Alaska Highway, thinking that it was the Trail to Heaven.

The Dreamer Charlie Yahey, told me something else about the relationship between vehicles and place. He said that the white men make the world smaller with their cars, trucks and planes. He said that they can do this because they power these machines with grease from the giant animals that Saya, the culture hero, placed beneath the earth in mythic time. His observation was a subtle reference to the story of creation. By exhuming the physical substance of that mythic time, the white men have taken the world back to a time when it was smaller and insufficiently interdependent. This story (which I also heard from Charlie Yahey) says that as the world grew from a speck of dirt under Muskrat's fingernail, the creator made a wolf and set it out to see if the world was big enough.

The wolf came back with a human arm in its mouth. The creator asked why Wolf had done such a thing, and Wolf replied that there was nothing else to eat. After that, the creator made moose and made another wolf. He sent the first one down beneath the earth. The second one never returned. By this sign, the creator knew that each animal had its proper food. The world was large enough to be self-supporting. With their machines powered by the grease of the giant animals, the white men have returned the world to a condition in which life is out of balance with its resources.

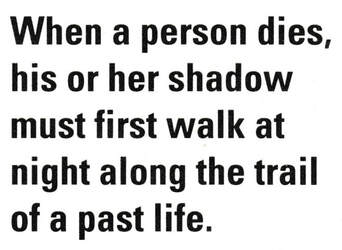

Place is important to the Dunne-za. They continue to struggle for the place they call “Where Happiness Dwells” because it reminds them of the people in Heaven who used to gather there. Heaven itself is a place of reunion “where happiness dwells.” People are happy when they learn from a Dreamer that a person who died recently has finally made it through. They know that when a person dies, his or her shadow must first walk at night along the trail of a past life. The ghost is blind at day but can see in the dark. When the Dunne-za were nomadic, they would avoid returning to a place to which someone who had died recently, might be returning. Now that they live on reserves, ghosts have become more of a dangerous presence than they were in the past. A person's ghost must literally touch down upon every footstep taken in life until at last it reaches the place at which it was light enough to rise along Yagatunne, the Trail to Heaven. Its journey is sequential and tied to the body's physical nature. It cannot be released until it comes to the place where it can rise like the spirit of a Dreamer. That is why the shadow's journey can be shortened if, in life, a person dances with others around a fire to the songs that the Dreamers brought back from their journeys along Yagatunne. People who dance along the circle of a common trail support one another. They give to one another in the same way that animals give to people who respect their bodies.

The Dreamer Charlie Yahey, told me something else about the relationship between vehicles and place. He said that the white men make the world smaller with their cars, trucks and planes. He said that they can do this because they power these machines with grease from the giant animals that Saya, the culture hero, placed beneath the earth in mythic time. His observation was a subtle reference to the story of creation. By exhuming the physical substance of that mythic time, the white men have taken the world back to a time when it was smaller and insufficiently interdependent. This story (which I also heard from Charlie Yahey) says that as the world grew from a speck of dirt under Muskrat's fingernail, the creator made a wolf and set it out to see if the world was big enough.

The wolf came back with a human arm in its mouth. The creator asked why Wolf had done such a thing, and Wolf replied that there was nothing else to eat. After that, the creator made moose and made another wolf. He sent the first one down beneath the earth. The second one never returned. By this sign, the creator knew that each animal had its proper food. The world was large enough to be self-supporting. With their machines powered by the grease of the giant animals, the white men have returned the world to a condition in which life is out of balance with its resources.

Place is important to the Dunne-za. They continue to struggle for the place they call “Where Happiness Dwells” because it reminds them of the people in Heaven who used to gather there. Heaven itself is a place of reunion “where happiness dwells.” People are happy when they learn from a Dreamer that a person who died recently has finally made it through. They know that when a person dies, his or her shadow must first walk at night along the trail of a past life. The ghost is blind at day but can see in the dark. When the Dunne-za were nomadic, they would avoid returning to a place to which someone who had died recently, might be returning. Now that they live on reserves, ghosts have become more of a dangerous presence than they were in the past. A person's ghost must literally touch down upon every footstep taken in life until at last it reaches the place at which it was light enough to rise along Yagatunne, the Trail to Heaven. Its journey is sequential and tied to the body's physical nature. It cannot be released until it comes to the place where it can rise like the spirit of a Dreamer. That is why the shadow's journey can be shortened if, in life, a person dances with others around a fire to the songs that the Dreamers brought back from their journeys along Yagatunne. People who dance along the circle of a common trail support one another. They give to one another in the same way that animals give to people who respect their bodies.

In some societies, a myth is something that is untrue, but that people believe out of ignorance or wishful thinking. In the spiritual traditions of Indigenous peoples, myths are true stories. Myths provide a model or directory of a culture's accumulated knowledge. Unlike legends and tales, myths explain the fundamental realities of a primordial or essential time. They explain the present in relation to a time of fundamental truth. Mythic cosmologies are not attempts to explain in fantasy where factual knowledge of the “real world” is lacking, but are rather the opposite - statements in a metaphoric language about what people know of the interrelations between the natural, psychological and cultural dimensions of reality. Myths do not “give meaning” to experience. Instead, they disclose the meaning that makes experience different from mere sensation.

Mythic time is about primordial events that are not, like those of history, forever relegated to the past. Mythic time is alive and active in people’s lives and experiences, dreams and visions, ceremonies and artistic creations. When myths tell about the world’s creation, they describe a process that is continuous and ongoing. The mythic image of creation describes a quality of renewal that is inherent in every moment of meaningful experience. In contrast to historical events which happen once and are gone forever, mythic events happen everywhere and always.

Mythic events return like the seasons. The events of history are unique and particular to their time and place. The events of historical time are like the events we experience with our senses. They materialize once and then are gone forever from our sensation. Mythic events are different. They are essential truths. They are of the mind, the imagination and the spirit. Yet, they are not imaginary in the sense of being without substance. Mythic events are metaphors. They stand for the ideas without which substance and sensation would be dead and devoid of meaning.

Dreamers, edgewalkers, or seers are adept at travelling through the geography of mythic time and space. The Dreamer, edgewalker, or seer's “magical flight” and spirit calling are usually described as taking place within a spiritual realm. In order to understand the meaning of this experience, we must find an adequate language of translation for it. What do we really mean when we speak of a spiritual realm? Oral traditions and stories held by Indigenous peoples and/or hunter-gatherer groups belong to an animist reality, and have shown clearly that they have detailed, intimate, and accurate knowledge of the natural world.

Magical flight and conjuring are inner journeys that recognize the transformation of sensation into experience. The three worlds of an animist cosmology are not geographical places; they are internal states of being, represented by a geometric metaphor. The seer does not fly up or down in the physical world. He or she flies inside to the meaning of experience. Magical flight enters a symbolic, internal, experiential dimension in which time, space, and distance as we know them, as well as the distinction between subject and object, merge into a unity. The magical flight delves into the center of things, a place where the four directions and the three worlds come together. It is not escape from the “real” world, but rather a flight from the ordinary world into the more profoundly real world of human experience and meaning. It is a flight inside to a spiritual center.

Mythic time is about primordial events that are not, like those of history, forever relegated to the past. Mythic time is alive and active in people’s lives and experiences, dreams and visions, ceremonies and artistic creations. When myths tell about the world’s creation, they describe a process that is continuous and ongoing. The mythic image of creation describes a quality of renewal that is inherent in every moment of meaningful experience. In contrast to historical events which happen once and are gone forever, mythic events happen everywhere and always.

Mythic events return like the seasons. The events of history are unique and particular to their time and place. The events of historical time are like the events we experience with our senses. They materialize once and then are gone forever from our sensation. Mythic events are different. They are essential truths. They are of the mind, the imagination and the spirit. Yet, they are not imaginary in the sense of being without substance. Mythic events are metaphors. They stand for the ideas without which substance and sensation would be dead and devoid of meaning.

Dreamers, edgewalkers, or seers are adept at travelling through the geography of mythic time and space. The Dreamer, edgewalker, or seer's “magical flight” and spirit calling are usually described as taking place within a spiritual realm. In order to understand the meaning of this experience, we must find an adequate language of translation for it. What do we really mean when we speak of a spiritual realm? Oral traditions and stories held by Indigenous peoples and/or hunter-gatherer groups belong to an animist reality, and have shown clearly that they have detailed, intimate, and accurate knowledge of the natural world.

Magical flight and conjuring are inner journeys that recognize the transformation of sensation into experience. The three worlds of an animist cosmology are not geographical places; they are internal states of being, represented by a geometric metaphor. The seer does not fly up or down in the physical world. He or she flies inside to the meaning of experience. Magical flight enters a symbolic, internal, experiential dimension in which time, space, and distance as we know them, as well as the distinction between subject and object, merge into a unity. The magical flight delves into the center of things, a place where the four directions and the three worlds come together. It is not escape from the “real” world, but rather a flight from the ordinary world into the more profoundly real world of human experience and meaning. It is a flight inside to a spiritual center.

Mythic thinking links the individual intelligence we all have as members of a common species with the collective intelligence of a cultural tradition. The myths of people who live as hunter-gatherers show them how to make sense of their experiences in relation to a natural world, of sentient non-human persons and natural forces. The myths explain that animals and natural phenomena are alive and thoughtful, in the same way that humans are alive and thoughtful. They show how the physical events of this world make sense, by reference to the essential events of mythic time. In the mythic world of animism, the world of local Indigenous Knowledge (IK), an event must be experienced as a thought, an idea, a dream or a vision before it can take place in physical reality. A widely distributed creation myth known to students of folklore as the “earth diver” story illustrates this principle. The story tells about how the world came into being as a speck of dirt that a diving animal brought up from the bottom of a primordial body of water. The story explains that the world came into being because a thought and an image of it already existed. Charlie Yahey told me this story as follows:

Yagesati [He-She sitting motionless at

the center of Heaven] first made the world.

Someplace there was a cross.

Yagesati made it and put it there.

There was water everywhere.

Yagasati is the one who wants it to

be like that.

Yagesati put that world in here.

When Yagesati put that world here

He-She sent some animals down to get a

little dirt.

The Creator sent Muskrat down to get

some dirt.

Muskrat dove down to get some.

Then Muskrat came up

holding some dirt here, under his nails.

Yagesati said to that dirt, “You will grow.”

From then, every year it got bigger

and bigger.

This “earth diver” story perfectly illustrates the essential features of an animist system of knowledge. Muskrat's speck of dirt is a world of substance that must be discovered at the center of a cross, the center of an idea that is motionless at the center of Heaven. Muskrat's dive gives depth to a two-dimensional world. He dives down into the cosmic center. He dives down into the center of an idea. He dives down to discover an idea at the center of things. He is the agent of a transformation of form into substance. He shows the possibility of diving from one level of cosmology to another. He is not just an animal. His dive is not just an event that may have taken place long ago. Muskrat is a metaphor. His story is active within every moment of experience. It reminds us that the world is continually being created. His dive stands for the human experience of transcendence and transformation.

Muskrat's dive to the nadir also suggests the possibility of a flight toward the zenith. It suggests the vertical dimension of an ancient cosmology. In Dunne-za tradition, this cosmic axis is known as Yagatunne, the “trail to Heaven.” The Dunne-za recognize their Dreamers, and describe them as being like Swans, the only animal who can fly from one season to another, and between Heaven and earth. Muskrat and Swan together complete two halves of a personality. Muskrat dives down to retrieve the world. Swan flies up to return to Heaven. Another Dunne-za myth tells about how a boy named Swan became a Dreamer and a Culture Hero through the transformative experience of his own vision quest. Even today, the Dunne-za find Swan in the constellation of stars we also know as Cygnus, the Swan.

Yagesati [He-She sitting motionless at

the center of Heaven] first made the world.

Someplace there was a cross.

Yagesati made it and put it there.

There was water everywhere.

Yagasati is the one who wants it to

be like that.

Yagesati put that world in here.

When Yagesati put that world here

He-She sent some animals down to get a

little dirt.

The Creator sent Muskrat down to get

some dirt.

Muskrat dove down to get some.

Then Muskrat came up

holding some dirt here, under his nails.

Yagesati said to that dirt, “You will grow.”

From then, every year it got bigger

and bigger.

This “earth diver” story perfectly illustrates the essential features of an animist system of knowledge. Muskrat's speck of dirt is a world of substance that must be discovered at the center of a cross, the center of an idea that is motionless at the center of Heaven. Muskrat's dive gives depth to a two-dimensional world. He dives down into the cosmic center. He dives down into the center of an idea. He dives down to discover an idea at the center of things. He is the agent of a transformation of form into substance. He shows the possibility of diving from one level of cosmology to another. He is not just an animal. His dive is not just an event that may have taken place long ago. Muskrat is a metaphor. His story is active within every moment of experience. It reminds us that the world is continually being created. His dive stands for the human experience of transcendence and transformation.

Muskrat's dive to the nadir also suggests the possibility of a flight toward the zenith. It suggests the vertical dimension of an ancient cosmology. In Dunne-za tradition, this cosmic axis is known as Yagatunne, the “trail to Heaven.” The Dunne-za recognize their Dreamers, and describe them as being like Swans, the only animal who can fly from one season to another, and between Heaven and earth. Muskrat and Swan together complete two halves of a personality. Muskrat dives down to retrieve the world. Swan flies up to return to Heaven. Another Dunne-za myth tells about how a boy named Swan became a Dreamer and a Culture Hero through the transformative experience of his own vision quest. Even today, the Dunne-za find Swan in the constellation of stars we also know as Cygnus, the Swan.

Another perspective on local knowledge comes from the Omaha Tribe of Nebraska. Unlike the Dunne-za, who traditionally lived in small bands of closely related people with no overall tribal organization, the Omaha are a formally organized tribe. During the 18th Century, they and four other tribes, known collectively as the Degiha Siouans, moved from a land of lakes and forests (probably in what is now Wisconsin) to the middle Missouri River country of eastern Nebraska, where they took up residence in earth lodge villages. During the summer, the tribe as a whole moved west onto the prairies to hunt buffalo. They camped in a circle known as the Huthuga. The Omaha symbolize their sense of place by cosmic symbols of a union between female and male, earth and sky, night and day. The tribe itself is made up of clans belonging to the “earth people” and “flashing eyes” or “sky people” moieties. Traditional Omaha ceremonies allowed people to visualize their connections to one another and the cosmos. The Omaha tribe centered itself in the idea of a cosmic union of complementary forces rather than in any particular place. They call the idea of life and motion Wakonda.

Ethnologists Alice Fletcher & Francis La Flesche, who wrote a study The Omaha Tribe in 1911, introduced the traditional Omaha ceremonies and institutions with an account of the religious and philosophical ideas on which they are based. These ideas suffuse every aspect of Omaha life. They provide “a point of view from the center” from which we may come to understand their meaning.

The tribal organization of the Omaha was based on certain fundamental religious ideas, cosmic in significance; these had reference to conceptions as to how the visible universe came into being and how it is maintained. The universal life force is conceptualized as Wakonda, described by Fletcher & La Flesche as follows.

An invisible and continuous life

permeates all things, seen and unseen.

This life manifests itself in two ways.

First, by causing to move:

All motion, all actions of mind or body,

are because of this invisible life.

Second, by causing permanency

of structure and form:

As in the rock, the physical features

of the landscape, mountains, plains,

streams, rivers, lakes, the animals,

and the humans.

This invisible life

is similar to the will power

of which humans are conscious

within themselves.

A power by which things are

brought to pass.

Through this mysterious life and power

All things are related to one another

and to the human.

The seen to the unseen,

the dead to the living,

A fragment of anything

to its entirety.

This invisible life and power

is Wakonda.

Wakonda is the spirit of life in the universe, “the mysterious life power permeating all natural forms and forces and all phases of man's conscious life,”[2] but it is not a spirit, even a “Great Spirit,” removed from human experience. Wakonda is within and around the conscious life of the universe, not from it. Wakonda “causes day to follow night without variation and summer to follow winter.” Wakonda is “an invisible and continuous life believed to permeate all things, seen and unseen.”[3] This life force animates all motion and dwells within all fixed forms. It may be seen in the world's changes and in its structures. It may be seen in the changes a person experiences in his or her life, and in the continuity that carries life on from one generation to another. Wakonda is the spirit of physical bodies in motion and the spirit that animates thought. It shows itself in the permanent structures of a physical landscape - “the rocks, mountains, plains, streams, rivers, lakes, the animals, and the humans.” It shows itself in the moving winds and resounding Thunders. It shows itself in the sun's path across the daytime sky, and in his momentary passage through the zenith point to become aligned with the earth's center. It shows itself in the fixed star of the night sky, the star around which all others turn. It shows itself in the wanderings of the planets. It shows itself in the structure of thought and in the mind's quick changes of mood. It shows itself in the cosmic union of male and female principles, each one giving to the other in order to create a completed whole.

Ethnologists Alice Fletcher & Francis La Flesche, who wrote a study The Omaha Tribe in 1911, introduced the traditional Omaha ceremonies and institutions with an account of the religious and philosophical ideas on which they are based. These ideas suffuse every aspect of Omaha life. They provide “a point of view from the center” from which we may come to understand their meaning.

The tribal organization of the Omaha was based on certain fundamental religious ideas, cosmic in significance; these had reference to conceptions as to how the visible universe came into being and how it is maintained. The universal life force is conceptualized as Wakonda, described by Fletcher & La Flesche as follows.

An invisible and continuous life

permeates all things, seen and unseen.

This life manifests itself in two ways.

First, by causing to move:

All motion, all actions of mind or body,

are because of this invisible life.

Second, by causing permanency

of structure and form:

As in the rock, the physical features

of the landscape, mountains, plains,

streams, rivers, lakes, the animals,

and the humans.

This invisible life

is similar to the will power

of which humans are conscious

within themselves.

A power by which things are

brought to pass.

Through this mysterious life and power

All things are related to one another

and to the human.

The seen to the unseen,

the dead to the living,

A fragment of anything

to its entirety.

This invisible life and power

is Wakonda.

Wakonda is the spirit of life in the universe, “the mysterious life power permeating all natural forms and forces and all phases of man's conscious life,”[2] but it is not a spirit, even a “Great Spirit,” removed from human experience. Wakonda is within and around the conscious life of the universe, not from it. Wakonda “causes day to follow night without variation and summer to follow winter.” Wakonda is “an invisible and continuous life believed to permeate all things, seen and unseen.”[3] This life force animates all motion and dwells within all fixed forms. It may be seen in the world's changes and in its structures. It may be seen in the changes a person experiences in his or her life, and in the continuity that carries life on from one generation to another. Wakonda is the spirit of physical bodies in motion and the spirit that animates thought. It shows itself in the permanent structures of a physical landscape - “the rocks, mountains, plains, streams, rivers, lakes, the animals, and the humans.” It shows itself in the moving winds and resounding Thunders. It shows itself in the sun's path across the daytime sky, and in his momentary passage through the zenith point to become aligned with the earth's center. It shows itself in the fixed star of the night sky, the star around which all others turn. It shows itself in the wanderings of the planets. It shows itself in the structure of thought and in the mind's quick changes of mood. It shows itself in the cosmic union of male and female principles, each one giving to the other in order to create a completed whole.

Wakonda is not a distant god. Wakonda is a comprehensive indwelling spirit of life and of thought. The lives of humans and animals alike “are animated by a life force emanating from the mysterious Wakonda.” In Omaha thought, “humans are viewed as one of many manifestations of life, all of which are endowed with kindred powers, physical and psychical.”[4] Wakonda is an intelligence, an “integrity of the universe, of which humans are a part.” As such, Wakonda has the authority of cause and effect. The person who fails to keep sacred vows, the person who lies, or the person who fails in pity and compassion, will be touched by Wakonda in the same way that the forces of nature come back upon a person who ignores them. Fletcher and La Flesche report:

Not only were the events in a person's life

decreed and controlled by Wakonda, but

man's emotions were attributed to the same

source. An old man said, “Tears were made

by Wakonda as a relief to our human nature;

Wakonda made joy and he also made tears!”

An aged man, standing in the presence of

death, said, “From my earliest years I

remember the sound of weeping; I have

heard it all my long life and shall hear it

until I die. There will be partings as long as

man lives on the earth - Wakonda has willed

it to be so!”[5]

The expression of emotion is an integral part of Omaha ceremony. The Keeper of a particular ceremony wept whenever there was a break in the ritual order for which he was responsible. He wept because he trusted that the compassion of Wakonda will always send someone to wipe away the tears.

Omaha people pray to Wakonda in times of need. “A man would take a pipe and go alone to the hills; there he would silently offer smoke and utter the call, Wakonda Hol......women did not use the pipe when praying; their appeals were made directly, without any intermediary.”[6]

Wakonda is emotion as well as intelligence. It is a compassionate as well as an intelligent integrity suffused throughout the universe. Wakonda is both compassionate to people and a reflection of the compassion that exists within them.

It seems appropriate to end with stories of beginnings. ln mythic time, beginning and end are inherent in every moment of experience. Whatever spiritual traditions may guide us as individuals, we each carry within us a speck of the world that Muskrat brought up from the primordial ocean of our beginnings as a species. The traditions of animism did not die with the rise of civilization and its “great” religious faiths. The world of nature is still alive with meaning. Indigenous traditions continue to offer us knowledge and power. “We are in need of that intelligence now as we have never been before. Our civilization has brought into existence the monstrous power of self-destruction. Our cultural intelligence has lost touch with the sapient intelligence we all have, as members of a species that is “wise and full of knowledge.” Although we possess exponentially increasing amounts of information, we are not necessarily any wiser or more full of knowledge than our Neolithic ancestors. Their spirits live as we continue to thrive on the planet they left for us, and we are responsible for the living planet that will give life to the generations that follow.

NOTES

[1] Fletcher, Alice C. and Francis La Flesche, The Omaha Tribe, Washington, 1911: Bureau of American of Ethnography, 27th Annual Report, p.134; p.597 [2], p.134 [3], p.599 [4], p.598 [5], p.599 [6]

Not only were the events in a person's life

decreed and controlled by Wakonda, but

man's emotions were attributed to the same

source. An old man said, “Tears were made

by Wakonda as a relief to our human nature;

Wakonda made joy and he also made tears!”

An aged man, standing in the presence of

death, said, “From my earliest years I

remember the sound of weeping; I have

heard it all my long life and shall hear it

until I die. There will be partings as long as

man lives on the earth - Wakonda has willed

it to be so!”[5]

The expression of emotion is an integral part of Omaha ceremony. The Keeper of a particular ceremony wept whenever there was a break in the ritual order for which he was responsible. He wept because he trusted that the compassion of Wakonda will always send someone to wipe away the tears.

Omaha people pray to Wakonda in times of need. “A man would take a pipe and go alone to the hills; there he would silently offer smoke and utter the call, Wakonda Hol......women did not use the pipe when praying; their appeals were made directly, without any intermediary.”[6]

Wakonda is emotion as well as intelligence. It is a compassionate as well as an intelligent integrity suffused throughout the universe. Wakonda is both compassionate to people and a reflection of the compassion that exists within them.

It seems appropriate to end with stories of beginnings. ln mythic time, beginning and end are inherent in every moment of experience. Whatever spiritual traditions may guide us as individuals, we each carry within us a speck of the world that Muskrat brought up from the primordial ocean of our beginnings as a species. The traditions of animism did not die with the rise of civilization and its “great” religious faiths. The world of nature is still alive with meaning. Indigenous traditions continue to offer us knowledge and power. “We are in need of that intelligence now as we have never been before. Our civilization has brought into existence the monstrous power of self-destruction. Our cultural intelligence has lost touch with the sapient intelligence we all have, as members of a species that is “wise and full of knowledge.” Although we possess exponentially increasing amounts of information, we are not necessarily any wiser or more full of knowledge than our Neolithic ancestors. Their spirits live as we continue to thrive on the planet they left for us, and we are responsible for the living planet that will give life to the generations that follow.

NOTES

[1] Fletcher, Alice C. and Francis La Flesche, The Omaha Tribe, Washington, 1911: Bureau of American of Ethnography, 27th Annual Report, p.134; p.597 [2], p.134 [3], p.599 [4], p.598 [5], p.599 [6]

Reprint from The Journal of Wild Culture, Spring 1989

Illustrations by Julia Blushak

Brian Fawcett (1944 - 2022) was a Toronto raconteur and author who was very active in the Canadian literary scene. Robin Ridington has worked with Dunne-za people since 1964. He is professor emeritus of Anthropology at UBC.

Pegi Eyers is the author of "Ancient Spirit Rising:

Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community"

an award-winning book that explores strategies for intercultural

competency, healing our relationships with Turtle Island First Nations, uncolonization, recovering an ecocentric worldview, rewilding, creating a sustainable future and reclaiming peaceful co-existence in Earth Community.

Available from Stone Circle Press or Amazon.

Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community"

an award-winning book that explores strategies for intercultural

competency, healing our relationships with Turtle Island First Nations, uncolonization, recovering an ecocentric worldview, rewilding, creating a sustainable future and reclaiming peaceful co-existence in Earth Community.

Available from Stone Circle Press or Amazon.