PEGI EYERS

To talk about the ambiguities we encounter in our re-indigenization process as white folks, let’s start off by asking - who is Indigenous? And how do we define indigeneity?

It has been said that we are all indigenous to place, but to guide us in these deliberations there is an established definition accepted today by First Nations, academics, social justice activists and many others. According to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues the term “indigenous” has been developed by extensive criteria including the following:

1. Self-identification as Indigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community as their member.

2. Historical continuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies.

3. Strong link to territories and surrounding natural resources.

4. Distinct social, economic or political systems.

5. Distinct language, culture and beliefs.

6. Resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments and systems as distinctive peoples and communities.

The UNPFOII criteria make it clear that indigeneity is based on more than just simple land occupancy, but is also defined as a specific community or culture that is informed by the land over a long period of time.

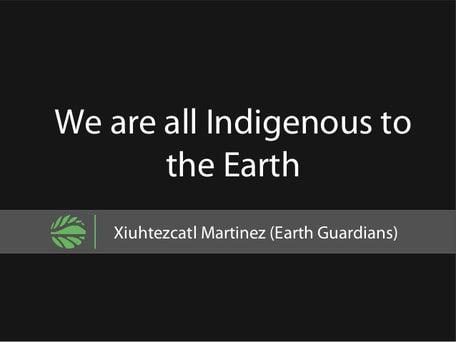

However, let's go on to consider what Encarta has to say on the term “indigenous.” The actual dictionary definition is “originating in and naturally living in a region or country, belonging to place.” Unfortunately in our rush to colonize the Americas, those of us in the European diaspora gave up our bonds to our places of origin, and our indigeneity as connected to those lands. However this does not change the fact that all land is sacred land, and the potential is always there to re-connect to the Earth, bypass the dominance of modernity, and go directly to the source of our eco-being. Despite the raging debate on extending the definition of the term “indigenous” to those of European descent, re-landing ourselves is of incredible importance in our mutual care for the Earth, and nativization in a bioregional context must be part of our essential uncolonization process. I would even go so far as to say that as members of Earth Community, it is the birthright of the entire human family to be indigenous to the Earth, and to appreciate and love the natural world. We must all face directly our innate need to be at one with wild nature, and to enjoy the blessings of Mother Earth and all her creatures as we go forward in this time of massive change.

A quotation from the Buddhist philosopher Derek Rasmussen addresses our dilemma. “What makes a people indigenous? Indigenous people believe they belong to the land, and non-indigenous people believe the land belongs to them. Can we commit to the land and each other? Let's hope so, because our current civilization is a one-time-only experiment. Once it has failed, we are going to have to re-braid ourselves back into the web of ‘all our relations’ - plant, animal and human. If there are future civilizations, they will be indigenous.” [1]

In my book Ancient Spirit Rising, I explore a set of place-based criteria that align with our embeddedness in nature. However separated by the human-built world, we are gifted at birth with the elements of air, water, earth and fire that are specific to the landscape around us. Inseparable from the archetypal patterns and intricacies of nature, we are imprinted with ions of air, fire in the form of energy from the sun, and especially the life-giving waters of a particular ecosystem. The molecules of the watersheds of our region are virtually found within our bodies, as these life-giving waters make up 60% of our physical being.

As children we are drawn to the natural world, and often our earliest memories are of time spent in green spaces with flowers, plants and trees. The same building blocks of organic matter such as carbon, oxygen and nitrogen that form the Earth and all Her creatures, also sculpt the human form. Unique to each individual, human beings also have an innate sensitivity to electrical and electromagnetic fields, and we are equipped with a multitude of sensory processes by which to interact with the other-than-human world. The biome is part of us, our bodies resonate with the energies of the earth, and it can be said that we are indigenous to place from the moment we are born.

Indigeneity has also been described as “belonging to ancestral land,” which means that many generations have come and gone, to mark their collective psychic and physical presence on the land. So by virtue of our buried ancestors and the spirits of our Beloved Dead that inhabit our psychogeography, how many generations does it take to establish deep connections? Two generations? Five generations? Ten? According to renowned author Leslie Marmon Silko, indigeneity is quantified by having at least a thousand-year presence in a specific place. However long we have been here on Turtle Island, our bonds to the landscape into which we have been born and/or are currently living, will always be preceded by the much deeper attachments of the original First Nations.

Based on our collective lack of care for the natural world, it is a Settler Sidestep to suggest a debate on the occupancy issue with Turtle Island First Nations. For example, my motherline in Ontario goes back to 1832, which is seven generations of interlopers being born on Turtle Island. If we define “indigeneity” by an extensive number of generations being born and reclaimed by the land, seven generations barely qualifies. Perhaps the "indigeneity debate" would be better served after Settlers have successfully healed our disconnect from nature and have become caring Earthkeepers and stewards of the land. Or at the very least, (as it is for all human groups worldwide) dedicating the bones of our Ancestors to the soil of our homeland(s) would make us responsible to that land.

This passage from Sirona Knight comments on on how our cultural and spiritual heritage becomes imbedded in the land. “Within the Celtic Spiritual traditions, the physical spirit and body of one’s Ancestors are given back to the land at the time of their death. In this way, the Ancestral energy, the sacred spirit of each person literally lives within the land, waiting to be called upon in ritual and ceremony.” [2]

We cannot deny that in a few generations, the spirits of our ancestors now inhabit Turtle Island. Yet the official meaning of “indigenous” (and rightly so) will continue with the baseline of the UNPFOII definition. Faced with paradoxes such as Indigenous peoples in privileged societies who have not been colonized, yet still have a long-standing ecological knowledge of their landbase, UNPFOII highlights the importance of self-identification, and that it is Indigenous peoples themselves who ultimately define their own identity as “Indigenous.” Right now, using the UNPFOII definition is integral to the legal cases on human rights and land claims being challenged in the courts by First Nations, which is the key reason why other groups (like white folks) should NOT be using it.

So we see that using the term “indigenous” to self-identify for us as Settlers is erroneous, and even more so when we consider the trend for non-native spiritual seekers to call themselves “indigenous” while continuing to incorporate the theft of Turtle Island Indigenous Knowledge and tools into their New Age, rewilding, transformational, Neo-Pagan or "shamanic" practices. Even more alarming are the white supremacists, both in Europe and the Americas, who are co-opting the terms “indigenous” or "nativism" to connect them to a place of origin, in order to perpetuate their metapolitical practices of racism, superiority, and white dominance over people of colour.

In my book Ancient Spirit Rising I respond to the genocidal effect of cultural appropriation by advocating for Settlers to recover their own ancestral-sourced knowledge, to reclaim an authentic ethnicity, and to use identity markers other than “indigenous.” Overall I use the terms “indigenous” and “re-indigenization” very sparingly, and uneasily I might add, in favor of the terms "pre-colonial," “ancestral knowledge” “heritage,” "ancestral arts" and “ancestral roots."

The continuing antithetical use of the term “indigenous” by white people in identity theft and cultural genocide has forced organizations such as CAORANN Council (Celts Against Oppression, Racism and Neo-Nazism) to label any white person who uses the word “indigenous” as an identity marker to be racist. An excerpt from the hard-hitting CAORANN Statement "On Indigenous Knowledge and Indigenous Identity" is reproduced here, as it carries much relevance to the controversy.

“Recently there is a movement on the part of some non-Natives - Americans, Canadians and Europeans - to identify as 'Indigenous European.' The first people to use this phrase were white supremacist groups, who are appropriating the term 'Indigenous' to make it seem like white people are somehow an oppressed minority. Others are appropriating it because they have racist stereotypes of Native people as all "mystical" and therefore white folks who call themselves 'Indigenous' are somehow more mystical too. We have seen non-Natives using this cloak of 'Indigenous European' in an attempt to colonize councils of actual Indigenous people, and to even lead and pretend to speak for real Indigenous People. We feel this is an act of racism and attempted cultural genocide. We are shocked and appalled at these attempts by non-Natives to displace and disappear Native Peoples, and we strongly advise non-Native people to shun the use of 'Indigenous' or 'Indigenous European' for ourselves or our spiritual traditions. We already have terminology, in our own languages, for our ancestral, earth-honoring ways; we don't need to steal terms and identities from brown people. From this point forward, if you are a colonist or a descendant of colonists who insists on calling yourself 'Indigenous' or 'Indigenous European' (or the ridiculous oxymoron, 'Neo-Indigenous') we will assume you are an appropriator and a racist.”

There is no mistaking the position of CAORANN, yet their claims on "Indigenous European" need to be challenged. Any description of "Indigenous Europeans" as members of the colonizer class in the Americas has to be separated out from those in Europe. There are genuine groups in many European countries who still live in the same homelands their ancestors have occupied for centuries, and are most definitely Indigenous to place (and fit the UNPFOII definition). Offshoots of functioning European cultures in the Americas such as the Gaeltacht Bhaile na hÉireann (the North American Gaeltacht), a designated Irish-speaking area in Tamworth, Ontario, have their own terms for self-identification, and would probably have no need to engage with the "indigeneity debate."

In any case, considering the outrage that is caused by the white use of the term “indigenous” it comes down to a question of personal ethics, and having a well-defined moral compass. Do we really want to add an extra layer of harm to First Nations by co-opting language that is not our own? There is no easy answer to this controversy, yet we can conclude that using “indigenous” as a term for self-identity is not the way to go. Instead of questionable practices, our re-landing should be synonymous with social justice, allyship, solidarity, and developing intercultural competency skills with First Nations, the original inhabitants of Turtle Island. Meanwhile, the genocide, oppression, human rights abuses and assimilation of First Nations continue to happen every single day in the Americas. It certainly makes our public debate on the term “indigenous” seem rather absurd, doesn’t it?

NOTES

[1] Derek Rasmussen, “Non-Indigenous Culture: Implications of a Historical Anomaly,” YES! Magazine, July 11, 2013. (www.yesmagazine.org)

[2] Sirona Knight, Empowering Your Life with Wicca, Alpha Books, 2003

| Read more on social justice, ethnocultural recovery, Settler re-landing, rewilding, ancestral connection, sacred land and animism in Ancient Spirit Rising: Reclaiming Your Roots & Restoring Earth Community by Pegi Eyers. PURCHASE LINKS Amazon.com www.stonecirclepress.com |